Astronomy

Painting the Lagoon Neblua

My first effort at using the iPad and Procreate to paint was the Eagle Nebula. To be honest I started that first project assuming I would not get very far. I’d never painted and expected it would be a huge mess. But it wasn’t half bad and I enjoyed the process far more than I expected I would. In fact I enjoyed it so much that when I finished I decided to try another, the Orion Nebula. When I finished that I thought I’d give the Lagoon Nebula a try. I chose the Lagoon Nebula because I’d recently viewed it as it is a great summer object and one I always view at least a few times each season.

Precarious

As is my usual routine I took my dog Cosmo out for our walk to the mailbox yesterday. Along the way I had a thought about the precariousness of our existence on Earth. We live in this sort of illusion as our daily life is wrapped in an assumption of stability. For the most part our human brains encounter the same environment everyday. Most of us wake up in the morning and are active during the day. The light from our sun scatters in our atmosphere, heating and lighting and otherwise presenting a world around us that seems stable. Somedays are cloudy, others sunny, often a mix of the two. As we go about our days we see a mix of human and non-human species, natural and human environments. We eat and breath, work, play, and talk.

But our life on this planet exists on the thinnest of onion skins. The biosphere of our planet, the zone in which all life happens is remarkably thin. While the actual thickness of the biosphere is not easily measured it generally falls within a range of 6.5 miles. At the highest we have birds flying as high as 1.1 mile and at the depth we have fish 5.2 miles below the water. There are examples of higher flying birds and deeper dwelling organisms but they are exceptions to the general. The diameter of the earth is 7,918 miles. The radius is 3,959 miles. Almost all life on our planet lives on the outer 6.5 miles of that.

As an amateur astronomer I’ve spent a good bit of time viewing and contemplating space and distance. For all of the beauty of the stars in the night sky, space is mostly empty. The space between stars is vast. The space between galaxies even more so. If we just turn our attention to our own solar system and what exists here well, again, it’s mostly empty space. Our Sun makes up 99.86% of the matter in our solar system. Our Earth, though it is the densest planet in the solar system, is only the tiniest proportion of the mass of our solar system. It barely registers. On the scale of our solar system our Earth is merely a tiny point separated from the sun and other planets by vast distances. To get a sense of it watch this amazing video by Wylie Overstreet in which three guys drove out to the desert of Nevada with a to-scale model to demonstrate the spacing of our solar system.

Our lived experience, our world, is just a precarious, thin layer on what amounts to a very tiny planet. On a clear, dark night I can lookup and see several thousand stars with my naked eyes. In remote locations such as mine there is little light pollution and the atmosphere disappears. It is in this star-lit darkness that I can begin to experience the Earth as a space ship of sorts. It really is a living space ship. In our orbit around the sun we move through space at 67,000 miles per hour. But remember, our solar system is also moving around the center of the Milky Way galaxy at 490,000 miles per hour. Of course we don’t see it or feel it directly but it is happening nonetheless.

Life on Earth is precarious. It’s stability is not permanent. Our sense of day-to-day continuity is something we’re used to and something we assume will continue. I’d suggest that if more people had a better sense of how it all works, had a better sense of just how thin the envelope of safety is, perhaps they might be more inclined to take seriously the warning of science regarding climate change, habitat loss and other aspects of biosphere stability. It’s too late to stop much of what we’ve set in motion but if we don’t make real change very soon we will experience the worst case scenarios.

Finishing the Herschel I program

In the fall of 2012 I bought my first telescope since having one as a kid. I wasn’t sure how much use I’d get out of it but I wanted to give it a go. I suspected I’d not regret the purchase. Within the first couple of weeks I’d become obsessed. I went out each clear night and sometimes stayed up till I started dozing at the scope which was often in the wee hours of the morning. Within a couple weeks I’d started keeping track of the objects I was viewing. I started just with the date, object name/ID, date and time. Soon after I started noting the eyepiece I was using as well as a description. It occurred to me that it would be fun to do the full Messier list and get the certificate from the Astronomical League. Not that I cared all that much about the recognition but having a list helps give a bit of order to the process. Had I not taken it on I might have gotten stuck looking at the same objects. Another side effect of having a list and doing the “official” program is the requirement that the observer find the objects on their own. No go-to telescopes allowed. Which was not as much of an issue as I didn’t have a go-to telescope. But reading about the program drew my attention to the idea of systematic searching and recording.

A month into the Messier list I realized there were some nights that when I would have no objects to search for as I would have already found all the available objects on the list that were up in the sky. So it occurred to me to look for another list that I could start at which point I became aware of all the various programs that the Astronomical League administers. I settled on the Herschel I and got started. It’s a list of 400 objects from the NGC catalog of 7,840 objects, largely based on the observations of William Herschel, his son John and his sister Caroline. It’s a mix of galaxies, star clusters and various kinds of nebulae. It’s a great list to do after the Messier list because it is slightly more difficult with fainter objects.

I finished up, or thought I did, about a year later. Upon checking my list though I discovered that I’d bungled a few by not recording proper descriptions and I was also missing a few. So, I started filling in my gaps until, about a year later, I thought I was finished. And, again, I discovered a few I had missed! So, back to it. With each successive check my list of missed objects was getting smaller. Essentially my transition from the initial list to spreadsheet to database introduced a few errors. Over the past couple of months I’ve been taking care of the few remaining objects and in the wee hours of a late September morning I finally got the last object in my eyepiece. NGC 2372, a planetary nebula in Gemini. I entered it in to my report and spent the rest of the morning double checking my final list. All in all the list took about four years and during that time I recorded well over 500 observations for that particular list (many duplicates due to the first 100 or so having been recorded without the detailed descriptions).

What did I learn during the experience? I learned much more about seeing the objects. Early on I was moving too quickly from one object to the next. It was not uncommon for me to log 15 objects in a 4 or 5 hour session. That’s three to four an hour. When you consider the time it takes to find an object in the scope and record the observation it turns out I was only looking at some objects for 5 minutes or so. That’s a minimal amount of time. These days I tend to look at about half that number of objects and I spend more time on each one.

The process of really seeing a faint object requires dark adapted eyes (no bright lights after you start viewing. Only low levels of red light!) and it requires at least 10-15 minutes, often times more, for each object. I also find it helpful and more educational if I take some time reading about the object. I don’t necessarily see the object better but reading about it helps me appreciate what I’m seeing. It’s easy to do using Sky Safari which is my preferred astronomy app. Each object has a description associated with it, many of them are quite detailed. There are also images in the app which can be very helpful in finding some of the details that might otherwise be missed.

I also was also reminded that there is an important connection between observation, vocabulary and description. As with any skilled observation it is important to develop an understanding of the components of what is being viewed. For example, if I’m viewing birds I pay attention to not just the colors but also the shape of the beak and tail, the physical habits, the body shape, the song, etc. There are many details that will help me identify the species of bird I’m looking at as well as understand something about the bird for example it’s diet or food gathering habits. The same might be said of plants, trees, butterflies or any other observation of the natural world including astronomical objects. There is a certain literacy that goes with observation and increased literacy means a more detailed interpretation of the sensory data.

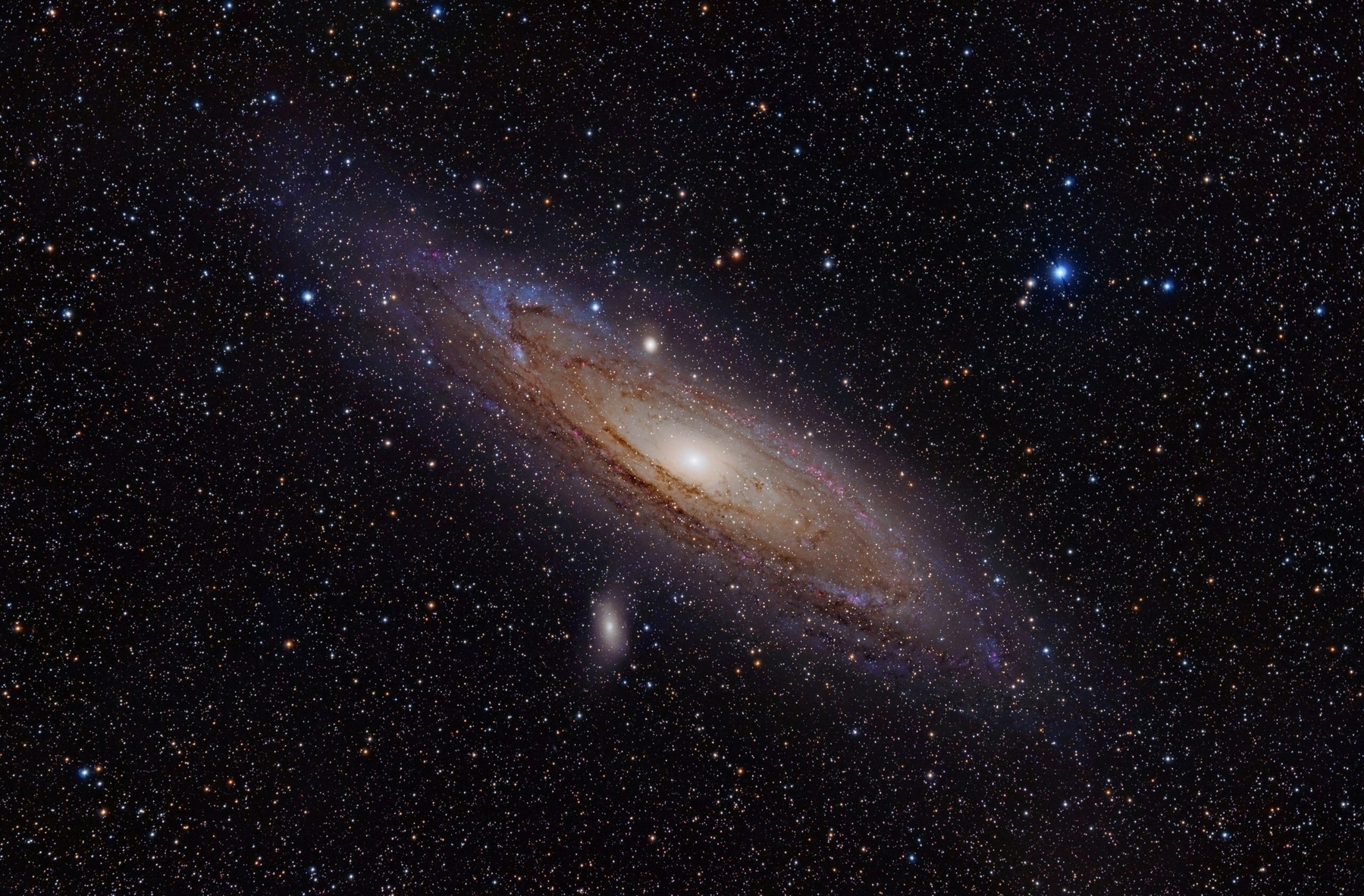

When I first began looking at galaxies I mostly just saw smudges of light. But right off it was evident that the shapes varied. For example, the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) and it’s two neighbor galaxies (M32, M110) vary quite a bit in size, shape, brightness and features. They’re a good starting point and learning tool. M31, a spiral galaxy, fills even the largest wide-field eyepiece with its large disc and offers a concentrated, bright nucleus as well as dust lanes. By comparison, M32, an elliptical galaxy, appears as a compact and bright nucleus with no disc. M110 is also an elliptical galaxy but is much larger than M32 and better described as an oblong nebulosity with a slightly bright central area but no bright core or nucleus. But while these three nearby galaxies are a good starting point and each offer different characteristics to be described they are just the beginning of many galaxies. Then there are the many kinds of nebulae and star clusters to learn about. No doubt astronomy offers many years of possible observation, a lifetime of possibilities in fact.

So, where to next? I’ve already started three other programs: double stars, nebulae, and the Herschel II list. I think I’m going to start the lunar program as well. As our closest neighbor the moon can cause a great deal of light pollution for much of each month making other observations difficult. But it’s a fascinating subject itself, why not enjoy it?!

Looking at other galaxies

One of the best things about living under really dark skies and having a decent telescope is viewing other galaxies. While I equally enjoy the many beautiful objects in our own galaxy such as nebulae and globular clusters, the hunt for distant galaxies has a meditative quality for me. Sometimes the finding is a bit of a let down. For example, last night I went looking for NGC 7042, a spiral galaxy. It took some doing but I found it. It’s 250 million light years away. Yeah. It was the faintest little smudge of light barely detectable on a very clear night with a decently sized telescope (12.5 inches). When I find these really faint ones I always laugh at my disappointment. Yes, it is a galaxy filled with billions of stars and yes, I just sighed in disappointment. But, but, it’s 250 million light years away I remind myself. Not only that it is moving away from us at 5,083 kilometers per second or, 1.7% the speed of light. There will come a time in the distant future when that galaxy and others are no longer visible from Earth. The stretched out light will no longer reach us. The Universe is expanding and that expansion is accelerating. Eventually galaxies that are currently visible to us will blink out. Of course, by that time we’ll likely not be here to notice.

The thing about viewing other galaxies is that it helps frame the scale of the Universe. When I look at the star Vega I’m seeing a star that is only 25 light years away. Yes, still a vast distance from our perspective. But it’s in our local neighborhood so to speak. In fact, it’s like a neighbor on our own street. Funny thing, the stars we see when we look up without a telescope are all in our local neighborhood. We’re only seeing about 6,000 of the very closest stars in our galaxy of 200 billion stars. When I look at the Orion Nebula I’m looking at something that is only 1,400 light years away. Sure, that’s a good bit further than Vega but again, remember that our Milky Way galaxy is an average of 100,000 light years in diameter. So, Orion is still very much in our local neighborhood.

[caption id=“attachment_928” align=“alignnone” width=“2560”] The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest galaxy of the Local Group which consists of about 45 other galaxies including our Milky Way.[/caption]

The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest galaxy of the Local Group which consists of about 45 other galaxies including our Milky Way.[/caption]

But back to the viewing of galaxies, the easiest to view from the Northern hemisphere of Earth is Andromeda which is “only” 2.5 million light years away. It fills the eyepiece of my telescope and can actually be seen with the naked eye if you’re under dark skies. I have no problem picking it out from the stars of the Milky Way. It’s oval of faint light is actually quite large and fills an area larger than the full moon in our night sky. It’s quite close and in fact, billions of years in the future we will in fact merge with Andromeda. I viewed Andromeda just two nights ago. I also viewed the Bode’s galaxy, M81 and the Cigar Galaxy, M82 which are a pair of galaxies 12 million light years away and are fairly bright and easy to find with a telescope. In 2014 a star went supernova in M82 and we were able to view it from Earth. Quite a show! So the pair is, in the larger scale of things, quite close. A bit further than Andromeda but not nearly as far as the 250 million light years that makes NGC 7042 so faint.

Faint and distant or bright and close, viewing other galaxies is a thrill because it means looking at the starlight of hundreds of billions stars. As those photons stream into my eyes I’ve got a direct connection with the ancient starlight created by billions of suns. It is light that has been stretching through the Cosmos for millions of years and ends its journey in my eye. The experience is one which enhances my perspective and gives life on Earth an added dimension. In seeing such distant worlds I begin to contemplate and understand the scale of the Universe in a way I had not before. It has changed who I am as a human as well as my understanding of what it means to be human.

Painting the Orion Nebula

In the fall of 2012 I had my first ever look at the Orion Nebula through a telescope. Like many people I'd seen Hubble images which are obviously stunning. Also, like many that know their constellations, I had seen it with my naked eyes as one of the stars in the sword of Orion. But with a telescope of any size or even with good binoculars, the middle star of the sword emerges as the center of this fantastic nebula. It's the sort of object many amateur astronomers will revisit many times. I know I have. It's a winter object, often referred to as the gem of the winter sky and with good reason. Of all the nebula visible from the northern hemisphere, winter or summer, The Orion Nebula is the most distinctive in terms of size and contrast. It provides amateur astronomers an opportunity to train their eyes in the discernment of greater details. Provided the same seeing conditions, a first viewing for 10 minutes is likely to be improved with a second viewing for 10 minutes the same night or another. Look again a third time for 15 minutes and you are very likely to see more detail. With each subsequent viewing more details emerge. It's also an object that benefits from larger, better instruments. So, while I can view it with binoculars or a 6" reflector if I get a chance to view it with a 10 or 12" reflector I will see a great deal more especially if I've had numerous previous sessions with it.

I've not yet tried to sketch or paint the nebula while at the scope though I hope to do just that this winter. In the mean time I decided to give it a go as my second painting using Procreate on the iPad. My intent is to do a series of these in part to improve my painting technique and knowledge of Procreate but also to better learn the details of the object. Just as more time looking through the telescope results in noticing more detail, more time looking at and painting an image, does the same. With each painting I'm also spending more time reading about the object. Usually using a combination of the Sky Safari description in combination with the Wikipedia entry. Here's the entry for the Orion Nebula.

In total I've spent about 27 hours broken up into 5 or so sessions. Here's a look after about 16 hours:

At this point it was easily recognizable but still missing many details. I should mention that I have no experience painting on any medium. It may well be that this sort of project should have taken half the time. Or double the time. It may also be that I'm going about it all wrong. The gist of it is that I'm layering. I've got a layer of stars on the very top, another for the base nebula which is largely created with the airbrush and sits at the bottom. Then I end up with at least two layers of wispy nebulosity and yet one more which consists of the darkest nebulosity and sits on top. These are often the thickest, clumpiest bits of dust and gas which more completely block the light coming from behind. The thickest of these are often referred to as bok globules.

The next image represents about 22 hours. Lots of refinements and new details.

Much closer but still not there. It's hard to know when it's "done". I could have stopped at this point but many details were missing and some bits that I did have were not right. That said, it's a painting and not meant to be exact. I suspect that going forward I'll play with this idea of what's finished because there is no way to know. Especially with something such as this, my intent is to get something that very closely resembles the photographic image but which is still obviously a painted version. It's not necessarily a creative project as much as it is a documentary.

The last image was finished this morning. I thought I was finished last night. But upon opening it up noticed more details. And that's the thing of it. I made some changes this morning but could have kept going. I could have spent all day on it and tomorrow as well. There's always another wisp of gas to be painted. Another knot of darker gas. A missing star. An area of gas in which my color is off. So is it finished? Yeah, for now. It's time to take a break and then move on. Here it is after about 27 hours.

Of course it should be said that the photographic images vary. Not only can the color very but also the emphasis on stars or nebulosity can change (among other things). It depends, in part, on the spectrum in which the photo was taken. The electromagnetic spectrum is a wonderful thing consisting of a variety of wavelengths each of which is photons traveling at different energy levels. The lower energy wavelengths such as radio or microwave are longer and pass through gas and dust more readily thus images taken in those wavelengths will tend to allow more background stars through. Images taken at higher wavelengths such as the visible will tend to show fewer stars as the foreground gas and dust will block some of them. Here's the image I used for this painting, taken from the Wikipedia:

Painting the Eagle Nebula

A couple months back I started to see quite a few mentions of an iPad app called Procreate. It had been out for a couple of years but with Apple’s release of the iPad Pro and Pencil, Procreate was getting some new attention because it is an app specifically designed for painting on the iPad. I’m not a painter which is why I’d not given it more than a passing glance before. That said I have spent the past few years focusing more on increasing my graphic design skills, specifically vector-based work. I began with Illustrator because that is the industry standard. But have branched out to others because I don’t like Adobe’s subscription model. In any case, my time spent working in vector apps led to several for-fun illustration projects which has opened the door a bit to a larger creative flow. Enter Procreate and the idea of sketching or painting with an iPad.

I’ve not upgraded to an iPad Pro yet as my Air 2 is still quite fast and fully capable of doing what I do with it. I’ve never noticed the slightest bit of lag. So, when I started playing with Procreate it was not with Apple’s fancy new Pencil but with a generic $3 tablet stylus. It’s got a rubbery ball end that works much better than a finger for seeing where I’m touching the glass and allows for a much smaller point of contact. Nothing so accurate or fine as the Pencil but it still works pretty well.

[caption id=“attachment_908” align=“alignnone” width=“2480”] The Pillars of Creation[/caption]

The Pillars of Creation[/caption]

My first really go at something was unintentional. It started as a doodle of a book cover which had a close up image of the “Pillars of Creation” which is just one small part of the Eagle Nebula. Ten minutes turned into twenty which turned into an hour and then two hours. I couldn’t put it down. I spent the better part of a day and evening. And a couple days later I picked it up again to fix a few bits that were out of proportion which led to another evening. By the time I was “finished” I’d probably spent 15 hours on it. I’ve no doubt that someone with more skill could have done much better in less time but for me it was not only a learning process but I found it incredibly relaxing.

[caption id=“attachment_909” align=“alignnone” width=“2480”] The Eagle Nebula[/caption]

The Eagle Nebula[/caption]

A few days ago I’d gotten the notion that perhaps I should enlarge the project to more of the nebula. Yesterday I picked up the iPad, duplicated the file, and gave it a go. As before, the hours just flew by as I concentrated on the contact between stylus and glass. I think this second, larger painting was about 8 hours. I could likely spend another few hours on this and may yet do that. Something I’m finding with this kind of work is that it’s never really finished. There’s always something that can be changed. There are many, many details within an image like this that I could give my attention to. Also, this only represents a small portion of the much larger nebula. Perhaps that will be the next project.

The larger nebula:

[caption id=“attachment_907” align=“alignnone” width=“2500”] Image of Eagle Nebula[/caption]

Image of Eagle Nebula[/caption]

And, of course, the Wikipedia page for the Eagle Neblua!

Observing Mars

Mars. The Red Planet. We’ve made great progress learning about our neighbor in recent decades. We’ve currently got two active robots performing experiments and have had others. Imagery from Curiosity is incredibly detailed as is the science coming in from it’s ongoing collecting and processing of samples. I’ve mentioned before how easy it is to get lost in NASA’s Curiosity website.

But in terms of visual, amateur astronomy, I’ve only ever given Mars a cursory glance. If memory serves, it appeared as a off-white, pinkish disc. Nice to look at on occasion but nothing like a view of Jupiter or Saturn both of which offer surface details, moons and in the case of Saturn, rings. But Now I’m wondering if the fault was mine? Did I not look hard enough? I recently revisited the planet and saw surface details I’d not previously noticed. This was a view of Mars worth repeating more often!! A quick look in my preferred astronomy app for the iPad, Sky Safari, suggests that “In a small telescope, Mars shows many of the surface features that sparked the imagination of science fiction writers.” It may be that I was looking when local atmospheric conditions weren’t good or perhaps at a time when something was happening on Mars to obscure the details.

[caption width=“1300” id=“attachment_821” align=“aligncenter”] Observation of Mars June 5, 2016, 10:30pm. Sketched with Procreate on iPad. [/caption]

Observation of Mars June 5, 2016, 10:30pm. Sketched with Procreate on iPad. [/caption]

Now that I’ve had a good look and seen some detail I can say with certainty that I’ll be visiting the planet every chance I get. The surface details will change based on the season as well as the fact that a Mars day is 37 minutes longer than an Earth day which, if I’m thinking about this correctly, means that over time the side facing Earth will gradually change. In some ways viewing Mars is like a blend of viewing our moon and viewing a planet like Jupiter. By this I mean that, like our moon, we can observe features on the surface of the planet. But it’s not a static image. Our moon has no atmosphere and presents a static image to us. As with our observations of Jupiter, what we see with Mars will change over time. From month to month the view will change not only because of the difference in period of rotation but because of season and atmosphere. Fantastic!

Gravitational Waves Discovered

In case you missed it: LIGO announced the detection of Gravitational Waves

For the first time, scientists have observed ripples in the fabric of spacetime called gravitational waves. This confirms a major prediction of Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity and opens an unprecedented window onto the cosmos.A lot more at LIGO’s Detection Portal.

Gravitational waves were detected by the two LIGO detectors in Hanford, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana, United States, at 5:51 am EDT (0951 UTC). The waves were generated during the final moments of the merger of 2 black holes resulting in a single, massive, rotating black hole. Even though such a merger was predicted to happen, it was never observed before.

The merger of the two black holes happened more than 1 billion light-years away. (definition of a light-year, use this calculator to convert light-years to miles.)

Why is this discovery so important? Gravitational waves tell us a lot about their cataclysmic origins. They offer a unique way to look deep into the past and observe cosmic events that happened a very long time ago. Gravitational waves provide information about the nature of gravity that we wouldn’t be able to get any other way. With this observation, LIGO opens a new window through which we can study the cosmos.

Discovery 12.5 Dobsonian: Initial Thoughts

| Discovery 12.5" at its new home - many new deep sky explorations await! |

The scope and everything around it was with coated with a thick layer of frost. 19 degrees this morning but, thankfully, no wind. There were birds though, lots of chirpy birds. And a very pretty sunrise. And Jupiter which you don't see in this picture because the gas giant was out of the range of the photo, just a pinpoint of light high in the western sky. To the untrained eye the largest planet in our solar system would have looked like a star about to fade from view in the brightening sky.

I'm glad I got up when I did because had I waited another 15 minutes I might not have found it. As it was I had just enough time to tilt the scope over and place the Tetrad's red center point on the fading pinpoint. I was treated to the best view of Jupiter I've ever had. Even with the coming daylight I saw three bands of reddish clouds stretching across the white sphere of the planet. The two main bands even hinted at a bit of detail along the edges which exhibited irregularities. Even more, the white base color of the planet turned into a gradient of a fainter red over the north and south poles. Four moons were easily visible as pinpoints of light.

For a little treat after Jupiter I swung over to the moon (top right corner of the photo) and in its current crescent stage it's possible to see many more craters along the edge and it was a fantastic view.

This marks the 5th viewing session with the new scope. Well, new to me. It's actually about 14 years old. Handmade by the folks at Discovery Telescopes, it was a chance find on Craig's List. With a mirror of 12.5" it's only slightly larger than the Zummel's 12" mirror. I am not at all unhappy with the Zummel and have enjoyed it a great deal over the past three years but this was a chance at a better scope and thus a better visual experience at a good price so I went for it. Not only are the optics better but it came with an equatorial platform for tracking objects in the eyepiece. So, what are some of the differences and how does it perform?

Most importantly, the Discovery scopes are built with hand-made mirrors that are a step up from mass produced mirrors used in scopes by Zummel, Orion and others. Or so it is said. In terms of the visual experience I have to also mention that the Discovery is built using cardboard Sonotubes. Yes, cardboard. Very well painted and the Sonotube is very, very sturdy so this is not something that will bend or break easily as long as it is taken care of. But most importantly, the interior of the tube is pitch black. Unlike an unflocked metal scope that's been painted black but appears gray this is completely black. Set this next to the Zummel on a dark night and you'd be amazed at the grayish blue glow that you see when looking down the tube of the Zummel. Look down the tube of the Discovery and it is pitch black. The only light to be seen is that being reflected back up by the primary mirror at the base of the tube.

The result of the improved mirror and the blackened tube in the eyepiece is not just noticeable but dramatic. I can't say for certain how much of the improvement is the mirror and how much is the darker tube but I can say that in the five sessions I've had I am thrilled. As mentioned above, the view of Jupiter this morning was the best I've ever had. Did I think my views before were lacking? At the time, no. I was always very happy with them. But it is greatly improved with this scope. I'm looking forward to more viewings with darker skies and greater contrast. I suspect that for the most part the views will only be better.

Another object I've viewed during four of the sessions that needs special attention is the Orion Nebula. WOW. The view with this scope is nothing short of spectacular. When viewing astronomical objects, especially nebulosity, the key is contrast which translates into increased detail. With such low light the observer is always looking for the subtle details to be found in gradients of gray and usually blueish light. So, in an object such as the Orion Nebula which is easy to see even in binoculars the details emerge as you improve your practice viewing and as you observe with better equipment. I’ve had a good bit of practice and am seeing more all the time just because I’ve been looking at it now for 3+ years with several different scopes. In some ways it's like other visual activities that one learns in practice.

For example, as a bird watcher I'm still learning new things about birds and learning how not just identify them but to really see the details. With birds it's everything from the shape of the beak to the colorful feather markings, the shape of it's body, to the way the bird flies and more.

In visual astronomy practice helps one to see more details in any instrument but it also helps one notice the refined details in better instruments. If I were to look at the Orion Nebula with my 8" scope now I would see more than I did 3 years ago when I first looked using that scope because I know how too look. I know about averted vision and about spending enough time on an object. I know more of the details and about looking at dark areas as much as the light areas. So, regardless of instrument the view is always getting better with practice and familiarity. But with the Discovery I can safely say that I am seeing an amazing amount of new detail. The increased contrast means the subtle details that would have been lacking before now stand out. Differences in color and brightness mean differences in gradient which, in the case of this particular object, means a new sense of visual depth, of dimension. Honestly, this wasn't something I was expecting. Yes, I was hoping for a better view, better detail, but I didn't quite understand what that would be. Now I know.

Viewing the nebula now means seeing new detail everywhere which leads to this added sense of dimension. It's no longer a flat view. Now, I expect not all objects will benefit in the same way. In fact, I know they will not. My view of the Crab nebula is improved but not by much. It is a much dimmer object to begin with and as I understand it details only emerge with scopes larger than 16". I can't say that's true but I can say that my view is largely the same with all three of the scopes I have at my disposal: 8", 12" and the 12.5". In all three it is an irregular, somewhat spherical gray nebulosity that offers little to no detail. But M82, one of the two Bode's galaxies? I've not had nearly as much time with M82 with the new scope but in the brief time I've had I'd say it is improved a good bit. It might not prove to be as dramatic as the view of the Orion Nebula but it's definitely better. The same for the Andromeda Galaxy and the Triangulum Galaxy. My expectation is that objects such as galaxies that can offer a view of spiral arm structure will benefit a good bit which is great because they are some of my favorite objects to view. Some nebulae will be improved, others won't. I doubt larger open clusters of stars will be improved but I suspect the resolution of some of the fainter stars in some open clusters will be as will some globular clusters.

Viewing Comet Lovejoy

We finally got a chance to take advantage of the clear, moonless skies to have a look at Comet Lovejoy! Farra, Atira, Kaleesha joined me at the scope and it was quite a view. Fantastic I’d say. We also had a look at a few objects that Farra had not had a chance to see yet: the Andromeda Galaxy, Orion Nebula and the Starfish Cluster.

Homeschool Star Party

Wow. Just had a crowd of homeschool families from Poplar Bluff over for a star party. Denny manned the telescope, Farra helped guide the way up and down the path in the dark, Atira and Seth helped me in the house, making popcorn and hot cocoa and directing folks to the bathroom. I also quizzed the kids when they came in about what Denny had shown them. A wee bit hectic overall, as there were more than we were expecting, but quite a fun way to spend a winter’s evening.

Ultra High Res Portrait of the Andromeda Galaxy

The Milky Way Reflected

Original, high res version here: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/1409/AtacamaSaltLagoontudorica2320.jpg

Our Star

Fantastic image of our local star! Absolutely stunning.

The diameter of the Sun is about 109 times that of Earth, and it has a mass about 330,000 times that of Earth, accounting for about 99.86% of the total mass of the Solar System. Chemically, about three quarters of the Sun's mass consists of hydrogen, whereas the rest is mostly helium, and much smaller quantities of heavier elements, including oxygen, carbon, neon and iron.

The Sun is a G-type main-sequence star (G2V) based on spectral class and it is informally designated as a yellow dwarf that formed approximately 4.567 billion[b] years ago from the gravitational collapse of a region within a large molecular cloud. Most of the matter gathered in the center, whereas the rest flattened into an orbiting disk that became the Solar System. The central mass became increasingly hot and dense, eventually initiating thermonuclear fusion in its core. It is thought that almost all stars form by this process. The Sun is roughly middle age and has not changed dramatically for four billion[b] years, and will remain fairly stable for four billion more. However, after hydrogen fusion in its core has stopped, the Sun will undergo severe changes and become a red giant. It is calculated that the Sun will become sufficiently large to engulf the current orbits of Mercury, Venus, and possibly Earth.

Rhubarb and Sam, Episode 4

This week in Rhubarb and Sam, astronomy! We set-up at the Tucker Creek observatory for some time at the telescope only to have a clear night turn into a not-so-clear night due to high humidity. The stars were still pretty bright in our dark skies so we settled in on the moon couch (our disc shaped outdoor couch) to record an episode. From Cygnus to Sagittarius, Saturn to Mars, take a tour of our night sky with us. There's nothing quite like pondering our place in our galaxy and our galaxy's place in the Universe. Have a listen!

Links of interest:

Our Milky Way Galaxy

Our Solar System

Globular Clusters

Please note that you can subscribe to the podcast in several ways:

At the iTunes store via this link.

If you are using an RSS reader or podcast app use this link.

Thanks and enjoy!

Wonderland

There are moments in life when everything feels just right. I'm not sure if those moments are happening all the time and it is just a matter of seeing them, recognizing them and acknowledging them or if it is the act of recognizing the potential of their existence that we help them into existence. Whatever the case may be, I feel fortunate to have chosen a life, created a life, in which such moments seem to come often. If I had to guess I suppose I'd say that such moments become more numerous the more we are able to slow down, the more we are able to be in the moment with those around us. We had such a night tonight here at Make-It-Do.

Dinner was unusual in that I missed it. We always make it a point to sit together for every meal. All of us. But tonight I slept through it because I'd been up late at the scope and because we had a long day in the car which left my back aching. I napped until Kaleesha woke me after six. By that time the kids had gone off to play in the woods. Kaleesha had made the two of us salads for dinner so we sat on the back porch to eat. The sounds of life went on all around us. The chickens and goats were doing their thing and off beyond the goat yard the kids were at the edge of the woods playing. So many sweet sensations all mixing together: the wonderful food, the cool and unusual July temperature, the sounds of children and farm and conversation between the two of us made for a wonderful start to the evening. Shortly after dinner we were separated for a bit as she took a call from her mom and as she often does while chatting on the phone, wandered around the house taking care of little chores. She took care of the bread dough she'd started before dinner and, not long after, she put the rising loaves into the oven the smell of fresh bread filed the house. The kids continued to play in the woods so I picked up my book on the Herschel Objects and started reading, alternating between the book and a few articles on the iPad. At some point I got up for a bit of coffee and decided to hang LED string lights on the back porch. It's something we'd talked about doing just the other day in preparation for company coming Thursday night, so I thought I'd go ahead and get them up. By the time I'd finished the task the sun had settled in behind the trees and the kids had returned from their time in the woods. There's nothing quite as sweet as these kids telling the stories of such evenings. They described the work they'd done in cleaning a little patch of woods they sometimes play in and showed me the fresh callouses on their hands. They were excited and very pleased with themselves.

The bread was out of the oven and I was having another mug of coffee when we'd decided it was dark enough to get everyone ready to walk up the hill to the observatory. We've not taken much time to get everyone up here for viewing since we built the observatory. Mostly that is due to the seemingly never ending streak of cloudy weather which has meant observing time has been scarce. In recent days a couple of the kids have expressed a desire for scope time, so we jumped at the chance to share a clear night with them. As an amateur astronomer one of the greatest joys is sharing the beauty of the Universe. There's nothing quite like the reactions one hears when someone sets their eyes upon Saturn or the great globular cluster of Hercules or any number of other beautiful objects. Sharing it with kids is even better.

|

| The Tucker Creek Observatory. |

By the time we'd gotten the scope out it was just starting to get dark and Saturn was low in the horizon so I started with the beautiful ringed planet. Justin had the first turn and he seemed more interested than he's ever been. Most people, kids included, usually don't keep their eyes at the eyepiece long enough. I've noticed the same thing whenever I've taken a walk in the woods with others. More often than not, such walks seems to be a race to finish the walk with little time taken to really observe the details of everything on or near the trail. I suppose I'm not surprised. Our culture seems to emphasize quantity over quality, passive consumption over authentic engagement. This is a mistake, especially when it comes to amateur astronomy. Objects in the night sky are much better when viewed for a length of time. Our eyes take time to adjust to the dark and even after they are dark adapted more time looking through an eyepiece almost always allows for our brains to notice fine details.

Justin took his time. In fact, he seemed to be in no hurry at all as he focused on the planet.

“Do you see it Justin?”

“Yep.”

The scope moves easily and he has a tendency to bump in when he leans in, so I got on the ground while Kaleesha helped him at the eyepiece. From the ground I could look up the tube to the center red circle and keep the planet where it needed to be. Every 20 seconds or so we repeated the question to make sure he still had it in his view and each time he responded with “Yep.” He looked far longer than any of the other children; probably 2 minutes, maybe more. He was very attentive. Finally he pronounced, “Royal's turn!” and moved away from the scope. The kids all cycled through their turns at the scope, most of them offering some sort of excited acknowledgment of what they were looking at. From there we moved on to Mars which was just off to the west of Saturn. Royal requested that we look at the beautiful blue and gold double star Alberio in Cygnus. He remembered it from our very first time at the telescope in November 2012, so we moved to that next. From there we moved to the Ring Nebula and last the M13, the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules.

|

| The Ring Nebula image similar to that viewed in our 12" telescope. Our view has less color. |

The Ring Nebula, while not too flashy in the telescope, is a beautiful sight nonetheless. As with most astronomical objects the beauty is enhanced if some of the details are known. At the core of the nebula is a white dwarf star consisting of carbon and oxygen. Its mass is about 0.61–0.62 solar mass, with a surface temperature of 125,000±5,000 K. Currently it is 200 times more luminous than the Sun. Keep in mind that this is a star which is no longer in active nuclear fusion. It has exhausted its fuel and blown away the remaining gasses which form the ring nebula we see. The star is now just radiating heat and it is thought that such white dwarfs will do so for trillions of years. Source: [Wikipedia]

In contrast to the subtle beauty of the Ring Nebula, the Hercules Cluster, M13, is quite a sight and one of our favorites. Here's why:

Messier 13 contains several hundred thousand stars; some sources even quote more than a million. The brightest is the variable star V11, with an apparent magnitude of 11.95. Toward the center of M 13, stars are about 500 times more concentrated than in the solar neighborhood. While the probability of collisions between stars in such a crowded region is negligible, the night sky seen from a planet near the center of of this globular cluster would be filled with thousands of stars brighter than Venus and Sirius!

Unlike open clusters, such as the Pleiades, globular clusters are tightly bound together by gravity, and contain very old, mostly red stars. The age of M 13 has revised to 12 billion years - nearly as old as the Milky Way galaxy itself. Born before the Galaxy's stars had a chance to create metals and distribute them them in its star-forming regions, M 13's iron content relative to hydrogen is just 5% of the Sun's.

Source: Sky Safari App.

|

| M13 as it appears in our 12" telescope. |

It is a sight to behold. As the kids took their turns at the eyepiece on this last object I explained what they were seeing just as I had for the other objects. Justin, upon looking at the cluster simply said, “It's a galaxy!” We corrected him, knowing that while he may not understand the difference some of the other kids, Little Brook, Royal and Blue would likely pick up on it and would likely have a better understanding of the difference. There's something extraordinary about taking our time to explore the Universe with one another, especially when children are involved. Whether it is a globular cluster or a tiny frog, they are intensely curious. I continue to be amazed by the details they pick up on and the amount of information that they retain. While the youngest may not fully understand the difference between a galaxy and a globular cluster they certainly retain the information that they are different.

Just as exciting as our shared explorations is that they are actively investigating on their own time. The other day Little Brook saw a photo of a nebula as the kids were browsing through one of our astronomy photo books and excitedly proclaimed “That's the Horsehead Nebula!” This was something that she had learned on her own. Imagine a five year old learning to identify the Horsehead Nebula! Sometimes all I can do is shake my head and smile. As I sit typing this there are 3 day old ducklings happily chirping as they follow their momma just 10 feet outside my window. One room away Farra is working on some chain-mail armor and Blue and Little are speaking in very well done British accents as they play on the porch.

Yeah, I live in Wonderland.

Astronomy Outreach with the BSA

Lunar Eclipse

Cosmic Dance

A few weeks back I wrote about viewing the supernova in M82. It was first observed around the same time that an article was circulating about the continuing and drastic decline of Monarch butterfly populations. I had both the supernova and the threat to the Monarch on my mind when I sat down to write about my observation of M82 but I couldn't quite make the connection I wanted to make. A few days ago the Bad Astronomer, Phil Plait, in describing the earlier generations of star birth and death, comes close to articulating what it was I was pondering:

This happened in the Milky Way billions of years ago, and those elements from some long-dead star made their way into you. Your bones, your teeth, your blood, your very DNA have elements in them forged in the heart of a mighty star that violently tore itself to bits so that eventually you may live. It is a transformation on a literally cosmic scale.

I should hope the metaphorical metamorphosis is obvious enough. The only constant in the Universe is change, and much of it is a cycle. Birth, life, death, restructuring, and rebirth. That is also the theme of much of human art, from paintings and movies to myths and great novels.

Some say science is cold, dealing unemotionally with hard data. But that’s far from the reality. Humanity and life are reflected in the stars, and the Universe itself is poetry.

The thoughts I'd had were specific to the harsh reality of extinction on Earth. The Monarch is not there yet but it's numbers have declined drastically. Other species are also in decline and extinctions happen every day. In fact, according to the Center for Biological Diversity we are now experiencing the 6th mass exctinction event of the planet, loosing dozens of species a day:

It’s frightening but true: Our planet is now in the midst of its sixth mass extinction of plants and animals — the sixth wave of extinctions in the past half-billion years. We’re currently experiencing the worst spate of species die-offs since the loss of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. Although extinction is a natural phenomenon, it occurs at a natural “background” rate of about one to five species per year. Scientists estimate we’re now losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate, with literally dozens going extinct every day. It could be a scary future indeed, with as many as 30 to 50 percent of all species possibly heading toward extinction by mid-century .

Unlike past mass extinctions, caused by events like asteroid strikes, volcanic eruptions, and natural climate shifts, the current crisis is almost entirely caused by us — humans. In fact, 99 percent of currently threatened species are at risk from human activities, primarily those driving habitat loss, introduction of exotic species, and global warming. Because the rate of change in our biosphere is increasing, and because every species’ extinction potentially leads to the extinction of others bound to that species in a complex ecological web, numbers of extinctions are likely to snowball in the coming decades as ecosystems unravel.

For most of my adult life I've gone through a cycle of depression connected to or caused by my awareness of what we are doing to the planet and our fellow species. I will never accept what our species has done, is doing, to our planet but I have found a certain peace in the understanding that the Universe will go on regardless. Our fragile planet and the life on it has an end date. In 600 million years our sun will have have increased in luminosity significantly and the carbon cycle plants depend on will shift causing mass die-off of plant life and animal life. By the time the sun transitions from a main sequence star (4.5 bililon years from now) life on the planet will have long since disappeared. Such is the case for all life supporting planetary systems in the Universe. All stars have a limited lifespan.

The Monarchs will end. Humanity will end. Our planet, our solar system and our Sun will all have an end. So it goes. The cosmic dance will continue... for awhile anyway. What can we do but live our lives in the best possible way? I for one will try to live with a respect for the fragility of life on this Pale Blue Dot and with an understanding that the star stuff that makes up my body and this planet will one day be pushed forth into the Cosmos.

A Reassuring Fable

With the new Cosmos reboot coming, I present to you Part 3 of the Sagan Series.